Reflections on Tillyard’s The Elizabethan World Picture: Part Two

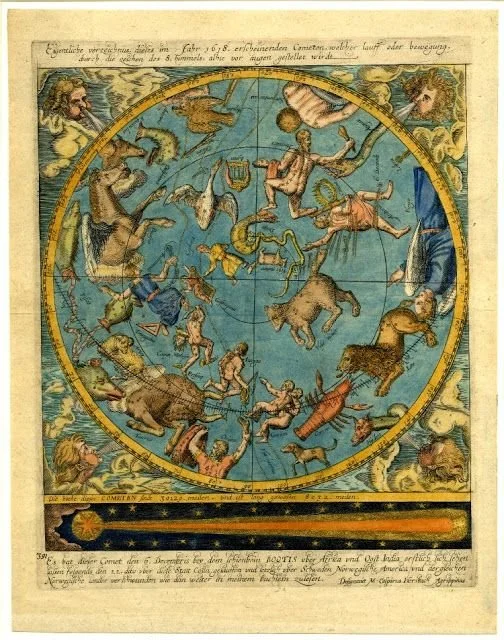

Celestial Globe with Comet. Caspar Hersbach (1618)

The Stars and Fortune.

The sphere of the fixed stars and the zodiac, as well as the seven planetary spheres (those of the Sun, Moon and five visible planets), were understood be composed of the “quintessence,” aether (EWP, p. 39). This incorruptible and immutable fifth element was first proposed in Plato’s Timaeus (58d; 360 BCE) and developed further in Aristotle’s On the Heavens (350 BCE) and carried forward into the Ptolemaic cosmological model (Almagest, 2nd century CE). Aether was introduced as an augmentation to the four classical elements (fire, air, water and earth), based on Aristotle’s reasoning that the stars and planets, due to their unchanging nature, could not be composed of the four corruptible elements in the sublunary sphere (EWP, p. 39).

The aetheric stars and planets were thought to communicate the will of the “Prime Mover” to the sublunary sphere (EWP, p. 52). This was, in fact, thought to be a very causal, almost mechanistic process in the cosmologies of Aristotle and Ptolemy (Tetrabiblos, 2nd century CE), made most evident in natural astrology (i.e., medical and meteorological). The notions of fate and fortune were integral to the Elizabethan worldview (EWP, p. 54).

It is important to note that the Roman Catholic Church differentiated natural from judicial astrology. Natural astrology, which dealt with forecasting medical and meteorological phenomena, was deemed an acceptable application of the art; whereas judicial astrology (genethlialogy/natal, mundane/omenic, electional/inceptional and horary) was deemed heretical because it undermined the central theological notion of free will, upon which salvation was predicated (Allen. Star-crossed Renaissance. Duke University Press. 1941. p. 148).

Preceding and flowing into the Elizabethan era, human character and disposition was thought to be influenced by the position and condition of the stars and planets at the time of birth (EWP, p. 52, 56-57). The geniture (natal chart) may therefore be considered a sort of schematic of the native’s character. This did not necessarily mean that the native was subject to the sort of deterministic fatalism advanced by, say, Stoic philosophy. Negative planetary and stellar/zodiacal configurations could be ameliorated by astrological magic (EWP, p. 53). This was not a new idea, as we find precedents of omenic mitigation as far back as the Akkadian Namburbi magical texts, which were meant to avert inauspicious portents (Caplice. The Akkadian Namburbi Texts: An Introduction. Undena Publications. 1974. p. 6). In fact, the very notion of magic itself, particularly of the astrological varieties, may well be seen as an extension of this sort of mitigation of fate and fortune.

Tillyard notes that Raleigh, in his History of the World (1614), seems to have struck a balance – indicative of the broader Elizabethan stance on the matter – whereby a “middle course” between cosmic determinism (which Tillyard, perhaps in reference to Plato’s “Myth of Er” (Republic. Book X), calls “necessity,” mother of the Fates) and free will may be envisioned (EWP, p. 56). Reason was set against the passions (EWP, p. 57) and, in the manner of Aristotle, man could reclaim his cosmic autonomy by acting in accordance with his character, which is an idea we see in Heraclitus’ famous aphorism: ethos anthropos daimon (“character is destiny.” Fragment 119).

Far from being seen as a cosmological prison, stellar and planetary fate was largely seen as a comfort to the Elizabethan mind (EWP, p. 16), as it supported the notion of an ordered cosmos – mitigating the ambiguous forces of chaos so apparent in the elemental tumult in the sublunary sphere.