Reflections on Tillyard’s The Elizabethan World Picture: Part Four

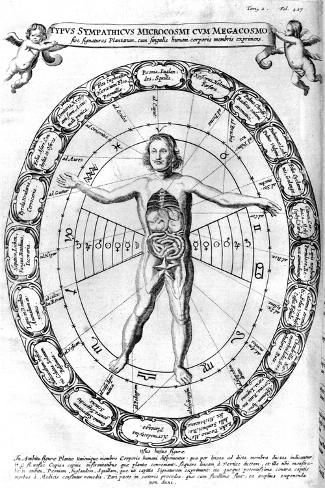

Utrisque comsmi...historia. Robert Fludd (1617-19)

The Microcosm and the Macrocosm.

As Tillyard illustrates, the sympathy and resonance between the macrocosmic universe and microcosmic man was of extreme importance to the Elizabethan cosmological perspective (EWP, p. 91) and to Renaissance humanism in general, which was particularly inspired by Marsilio Ficino’s translations of Hermetic and (Neo-)Platonic literature in the Florentine Academy. Numberless analogies were drawn between human physiology and cosmic organization; and it was by such analogies that man’s very sense of order was informed.

Platonism, Stoicism, Hermeticism and Neoplatonism all contributed to the establishment and proliferation of the microcosm/macrocosm paradigm. Undergirding this concept was the notion that the cosmos was itself alive (vitalism) and/or ensouled (animism). A cosmos possessed of mind and/or soul was advanced by Plato in his Timaeus (360 BCE). Central to this idea was the sympathetic relationship between the terrestrial and celestial spheres (see: the Stoic, Posidonius’ doctrine of cosmic sympathy, and the oft-quoted Hermetic axiom: “that which is below is like that which is above” from the Tabula Smaragdina, or “Emerald Tablet”). This doctrine is perhaps the most fundamental idea supporting astrology – that celestial events and phenomena are symbolically and acausally mirrored on the terrestrial plane and vice-versa.

Tillyard isolates various examples of this notion in Elizabethan literature and poetry (EWP, pp. 91-94), in addition to extending this idea into the political domain via the body politic. He makes mention of the ubiquitous motif of the roi soliel, or “solar king” (EWP, p. 89), as well as the terrestrial queen as being representative of the “queen in the heavens,” the Moon, “among the luminaries of her Court” (EWP, p. 90) and Elizabeth as “the mortal moon” (EWP, p. 105).

The body of man is teeming with “rivers” of blood, analogous of his veins and arteries; and internal “storms,” representing the mixture and separation of the humours and the perturbations of the passions, waxing and waning (EWP, p. 93). This is reminiscent of the astro-physiological (or, iatromathematical) doctrine of melothesia, in which signs and planets representative of the anatomy of man: the zodiacal sign of Aries to the head; Pisces to the feet (see: the homo signorum); as well as the planetary correspondences to the internal organs. We see early intimations of this doctrine in the work of Marcus Manilius (Astronomica, 1st century CE) and, later, a fuller treatment in Ficino (Three Books on Life, 1489).

Perhaps most importantly, at least to the Elizabethan mind, was the mirroring of cosmic order in society. This period, being relatively warless and witness to the proliferation of the arts – a “golden age” in English history, between the War of the Roses and the country’s Civil War – embodied the notion of beauty and order reminiscent of the very cosmos above. Momentarily, the confluent streams of Pythagorean cosmic harmony, the detached Aristotelianisms of the Middle Ages, and the platonizing effect of the early Renaissance found their own humoral balance in this optimistic moment in the history of the Western World.